Data is not as flexible as software, because data is persisted. Once there is data in a system, we cannot just change it, like we do it for software. To change data, code must be created to change it, and the data must be processed by that particular code. We must be very well prepared to cope with changes to data. This is why backend development is considered hard by some people.

Clean Code shines when it comes to evolvability of code. Specifically the Open Closed principle - often misunderstood - leads to extensible code, without modifying existing code. It is an intriguing question whether we can learn from Clean Code principle for data work.

This post gives the traditional definition of the Open Closed principle, as well as a simplified statement of it. An example for OCP compliant and non-compliant code is provided. Last, but not least, I generalize the principle and apply it to data work, just to derive an intristing insight: Theoretically, we can have black box checks, executed during runtime to find non-cohesive code.

Simplified OCP by the book

The principle was coined by Bertrand Meyer in his book about object oriented programming [1]. The following statements are important to be able to judge, whether the examples of this pos are expressions of the open closed principle.

Software entities (classes, modules, functions, etc.) should be open for extension, but closed for modification.

A module will be said to be open if it is still available for extension. For example, it should be possible to add fields to the data structures it contains, or new elements to the set of functions it performs.

A module will be said to be closed if [it] is available for use by other modules. This assumes that the module has been given a well-defined, stable description (the interface in the sense of information hiding).

To be able to later generize the principle to data, let me try to rephrase:

- Open Code

The functionality of existing code can be extended.

- Closed Code

Existing code is not supposed to be changed.

|

Note

|

The rephrased principle is a more strict statement than the original one, such that the following discussion are simplified. |

For our code base as a whole, we would like to add functionality by adding code, instead of altering existing code.

Strategy against OCP violation

There is a german website that is dedicated to Clean Code. It contains a set of practices and principles, nicely arranged by difficulty to master, and put into relation to few basic qualities, e.g. evolvability. OCP is good at making your code evolvable. The following example is just a slight modifcation of the example of the Clean Code website, such as translation to english. In this section, there is more explanation about the purpose and properties of OCP.

We will have a look at code that is non-compliant to OCP, as well as at code that is comliant to OCP. The compliant variant of the code is just a refactoring step away from the non-compliant code, and therefore expresses the exact same functionality. Then a requirement is presented and both variants are extended by this functionality. We will see, that the OCP compliant code behaves much better under change.

First comes the code that is not OCP compliant.

namespace OcpExample;

enum CustomerType { PartnerCustomer, OneTimeCustomer }

static class LibraryCode

{

const double PartnerDiscountFactor = 0.95;

public static double GetTotalPrice(CustomerType customerType, int amount, double price)

{

return customerType switch

{

CustomerType.OneTimeCustomer => amount * price,

CustomerType.PartnerCustomer => amount * price * PartnerDiscountFactor,

_ => throw new ArgumentOutOfRangeException()

};

}

}

static class NoOcpClientCode

{

public static void Behave()

{

Console.WriteLine(LibraryCode.GetTotalPrice(CustomerType.OneTimeCustomer, 3, 0.22));

}

}The class NoOcpClientCode is not part of the code under investigation. It is assumed that there is additional client code, such that all possible code lines thought the library code LibraryCode can occur.

The code that is compliant to OCP can be obtained from the previous code sample by applying the refactoring to replace an enumeration by the strategy pattern.

namespace OcpExample;

interface ICustomerPricing

{

double GetTotalPrice(int amount, double price);

}

class OneTimeCustomerPricing : ICustomerPricing

{

public double GetTotalPrice(int amount, double price) => amount * price;

}

class PartnerCustomerPricing : ICustomerPricing

{

const double PartnerDiscountFactor = 0.95;

public double GetTotalPrice(int amount, double price) => amount * price * PartnerDiscountFactor;

}

static class OcpClientCode

{

public static void Behave()

{

Console.WriteLine(new OneTimeCustomerPricing().GetTotalPrice(3, 0.22));

}

}|

Note

|

Did you see, how the cyclomatic complexity got reduced? |

Whether code complies to OCP or not shows itself when a new feature is added. Will we write a code block and add it to the code base? The we have OCP compliant code. Of course we can fake this argument, by just copying code, so I assume, we follow the DRY (Don’t Repeat Yourself) principle sufficiently well.

So let’s test our code with a probe requirement. A probe requirement is a Gedankenexperiment to strengthen the design of our code. Allow a specific type of customer that gets very good pricess, but pay a minimum price in case the do not buy as much as we require them.

|

Note

|

In physics probe charges are used to determine the field strength of, for example, a magnetic field. The field itself cannot be seen, since it is an abstract concept that just explains phenomena. In the magnetic field example that is the velocity of particles, considering high friction. It is tempting to compare the probe requirement with a probe charge. Then we can compare the OCP principle compliance with a field and the resulting velocities with characteristic code changes, such as non-invasiveness. |

Showing the changed structure of Listing 1 gives the following.

enum CustomerType { PartnerCustomer, OneTimeCustomer, MinimumPriceCustomer }

static class LibraryCode

{

const double PartnerDiscountFactor = 0.95;

const double MinimumPrice = 1;

public static double GetTotalPrice(CustomerType customerType, int amount, double price)

{

return customerType switch

{

CustomerType.OneTimeCustomer => amount * price,

CustomerType.PartnerCustomer => amount * price * PartnerDiscountFactor,

CustomerType.MinimumPriceCustomer => new double [] {MinimumPrice, price * amount}.Max(),

_ => throw new ArgumentOutOfRangeException()

};

}

}There are changes at three different positions. The enum has to be extended, the switch expression needs to be repaired, and what is worst: The LibraryCode class is added a constant, that is irrelevant to all previously existing code. The cohesion of this class just got reduced.

Doing this change in a production environment can already produce a little shudder.

Better would be, if code would just be added at a single code location, like when extending the functionality of Listing 2 as shown as follows:

class MinimumPriceCustomer : ICustomerPricing

{

const double MinimumPrice = 1;

public double GetTotalPrice(int amount, double price) => new double [] {MinimumPrice, price * amount}.Max();

}The cohesion of the existing structures is untouched and the cohesion of the new class is as it should be: High.

The probe requirement that we used cannot be used to proof that code is OCP compliant. Consider the following probe requirement: Add a discount on the number of articles that are bought. Both, Listing 1 as well as Listing 2 would be needed to change invasively, as opposed to extension without modification. Generally speaking, code can never be totally OCP compliant, if it actually does something useful. It is probably always possible to invent an addition of functionality such that the corresponding code change is an alteration and not an addition, thus, breaking the Open Closed principle. So choose your probe requirements wisely, and take many of them.

If it turns out that your code is not compliant to OCP with respect to the current requirement, it is likely possible to refactor it to be adhere to OCP, before you actually start to add new feature. Just recently, a collegue argued that the application of a specific feature flag to the code base is ridiculous, since it would need to be applied to 27 code locations. His situation can be refactored towards an OCP compliant code with respect to the new requirements, though, such that the variability that is introduced by the new feature is located in just one place, and afterwards replacing it by a dependency in the form of an interface. The, the feature flag can be added, even without modifying any existing code.

Synergetic data changes

Data always has to be thought together with code. Data is created, changed and deleted by running code. Whether the code that manipulates data is OCP compliant or not has no effect on the data itself. What does it even mean that data is OCP compliant? For this, let’s try to specialize the general principle Open Closed principle to data.

Review the OCP statements.

- Open Code

The functionality of existing code can be extended.

- Closed Code

Existing code is not supposed to be modified.

For data, this might mean the following:

- Open Data

The information of existing data can be extended.

- Closed Data

Existing data is not supposed to be modified.

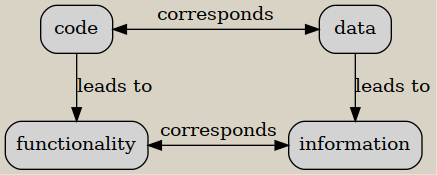

Or, to express the analogy in a symbolic language:

I believe that information is a good analog to functionality, since both, information and functionality, represent the business/user perspective of data and code, respectively. We can define information of a data instance as the set of statements that we are able to formulate about the data considering its context. The context of data is code that operates on that data, and the data that this code can operate as well.

Code is data

Source code is just data. As soon as code complies to OCP, then its corresponding source code does as well. Language of the scheme and lisp family live that even on a less technical level considering bytes: A source code file ultimately represents a nested list, a data structure that clearly represents data.

A slightly less trivial example is an External Domain Specific Language. In this case, data files that are external to interpreter code are used to modfiy functionality. DSL is the ultimate pattern for creating code that is OCP compliant, namely, the interpreter code. Functionality of what the interpreter does can be extended too a wide variety without touching the interpreter itself. But it is not necessarily Data OCP. Of course, if code is data, then the interpreter is data and the DSL is data, and it is clearly Data OCP.

Data types are data

The word data type can be confusing when talking about it in the context of programming, because types in object oriented programming not only contain fields with data, but can also contain functions. I would like to focus this discussion on data schemas. A schema basically is either a primitive type or a list of fields, each is of a specific schema.

Schemas can be database schema, explicitly defined schema in a schema registry, or implicitly defined schema by being able to let a piece of code process an instance of that schema without errors.

Then the following operations are Data OCP, considering that code changes to data schemas are data changes as well.

-

Add an optional field is added to an existing data structure with a default. All existing instance of such a data schema get this new information.

-

Remove an existing field from a schema. That field in existing instance have no meaning anymore.

-

If data references other data, than its information can be extended by extending the other data schema. Such schema are not part of the schema of the referencing data, because the reference is represented as a key.

If information originates from the code that runs it, and a data schema is implicitly defined by the code that runs it, then the above statements are almost a tautology. It essentially says that when we change functionality of the code that processes data of a specific type, then the datas information is changed, which is the definition that I gave above.

For more abstract/conceptual schema definitions, we have to rely on our subjective interpretation of meaning of data.

Reflective/dynamic code is able to cope with arbitrary schemas. Then the functionality of the code depends on the data instances that we feed the code with. This is true for DSLs for example. If there is such reflective code with respect to some data D1, that also consumes other data D2, then the information of the D2 is changed. That means, it is the combination of code and how code processes data with other data that determines whether data is Data OCP. It is code that can be classified Data OCP, not the data itself.

For example consider the following data structures, formatted in python:

D1 = { "key": "a" }

D2 = { "a": 5, "b": 7 }Are D1 and D2 Data OCP? Well …

def be_ocp(d1, d2):

return d2[d1['key']Considering the function be_ocp as the context of D1 and D2, they are Data OCP, because the information that results (the return value of be_ocp) changes for different D1 for the same D2. This example is somewhat trivial, and we might ask the question whether our code is always Data OCP, as soon as we have more than one data structure. I would say that this is not always the case, but good code should fulfill it. If code is not Data OCP, it means that multiple data instances are processed independently from each other, which in turn means that the code under consideration is not very cohesive.

|

Note

|

It is even possible to talk about Data OCP in the case of having only a single argument to a function, because the argument usually is a composition of multiple field. The field may be Data OCP compliant with each other or not. |

Summary

The Open Closed principle might help us identifying code that will not survive the drag of time. There are patterns readily available that support the OCP, such as the strategy pattern, or the usage of interfaces to delegate parts of the functionality to other code locations (Dependency Inversion principle). Such patterns contribute to better maintainability by reducing the cyclomatic complexity. The design hardens since code cohesion improves.

Breaking OCP leads to the unsettling situation that changes have to be done at multiple code locations. With feature distributed across many code locations, the probability that unit tests cover each case decreases. This situation is the default in many code bases! Very often it is possible, though, to first refactor the code with simple refactorings into an OCP compliant state, such that features can be added in a similarly safe way as in Listing 4.

Practically working with OCP means to do Gedankenexperiments by mentally applying probe requirements. Best those requirements are realistic and even have a chance to be planned during prioritzation. If requirements can be implemented effortlessly, the probability increases significantly that a product manager decides to buy it.

The OCP interpreation for data is only possible by considering that datas context, which is the precondition for giving it information. Information of data can be modified by modifying schemas, which can be data itself. The data’s context - code - determines whether data is Data OCP. When we are tempted to call data being Data OCP, we really say that the code is Data OCP. If code is not Data OCP, then it is either a projection, or it is not cohesive.