While writing my theory blog post about the Open Closed principle Unveiling the Open Closed Principle on Data Work, I came across three examples in which the Open Closed principle was broken, and negative consequences were visible.

In all three cases, the Catalogue Pattern was used, which I consider a code smell. For each case, I will present

-

the instantiation of the catalogue.

-

the negative consequences that we observed in this particular case.

-

how an OCP compliant variant looks like that resolves these consequences.

Generating telemetry events

Event Catalogue

When collecting data for a telemetry event, there is some data that is present for any telemetry event, irrespective of which functionality we want to collect data for. This can be, for example a user and a subscription identifier. Say, we collect information about a feature, for which it is interesting for product management to know the time duration until something is delivered. Then we might construct the following event DeliveryEvent and an interface IGenericEvent that represents the data that is independent of the specific feature:

interface IGenericEvent

{

public Guid UserId { get; }

public Guid SubscriptionId { get; }

public string EventType { get; }

}

class DeliveryEvent : IGenericEvent

{

public Guid UserId { get; set; }

public Guid SubscriptionId { get; set; }

public string EventType { get; set; }

public TimeSpan DeliveryDuration { get; set; }

}As soon as we want to create such an event, a dependency is needed that can deliver us the generic entries (UserId and SubscriptionId) in addition to the actual feature specific information, DeliveryDuration in this case. It is tempting to create a class as follows:

interface IProgramContext

{

public Guid UserId { get; }

public Guid SubscriptionId { get; }

}

class EventBuilder

{

private readonly IProgramContext _programContext;

public EventBuilder(IProgramContext programContext)

{

_programContext = programContext;

}

public DeliveryEvent TrackDelivery(TimeSpan deliveryDuration)

{

return new DeliveryEvent {

UserId = _programContext.UserId,

SubscriptionId = _programContext.SubscriptionId,

EventType = "Delivery",

DeliveryDuration = deliveryDuration

};

}

}This builder is very convenient to use. At the client side, it is a matter of calling a method to create the event needed.

If the code is to be extended by an additional event for a different feature, then not only a new class is created that implements GenericEvent, but also a new method is added to the existing class EventBuilder. This extension break the Open Closed principle. To avoid OCP violation, it is also possible to rename EventBuilder to DeliveryEventBuilder and create a new builder class for the new feature event, but this would violate the DRY (Don’t Repeat Yourself) principle and produces a lot of boilerplate code.

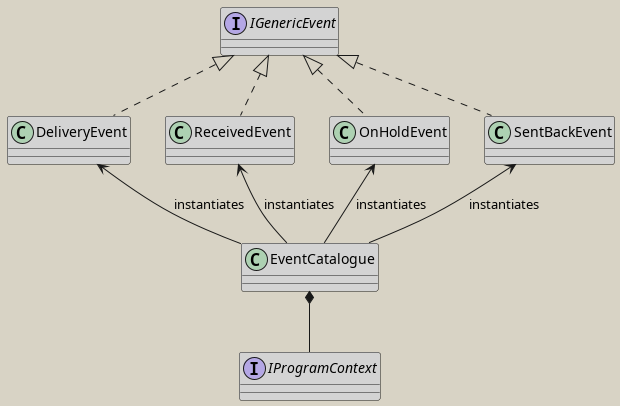

The EventBuilder will end up as a catalogue. Consequently, I renamed EventBuilder to EventCatalogue.

class EventCatalogue

{

private readonly IProgramContext _programContext;

public EventCatalogue(IProgramContext programContext)

{

_programContext = programContext;

}

public IGenericEvent GetDelivery(TimeSpan deliveryDuration)

{

return new DeliveryEvent {

UserId = _programContext.UserId,

SubscriptionId = _programContext.SubscriptionId,

EventType = "Delivery",

DeliveryDuration = deliveryDuration

};

}

public IGenericEvent GetReceived() { throw new NotImplementedException(); }

public IGenericEvent GetOnHold() { throw new NotImplementedException(); }

public IGenericEvent GetSentBack() { throw new NotImplementedException(); }

}To summarize:

When using the code Listing 2 as a starting point, it is actually not straightforward, how to refactor the code to avoid the catalogue. One possible solution would be to fill the implementations of IGenericEvent just by the feature specific properties, and use a single method that enriches those events by the UserId and SubscriptionId. That catalogue would be gone, but another principle of good design would be broken. Events are value objects, as opposed to entities, and value objects are expected to be immutable!

|

Note

|

The concept of value types and entities are taken from Domain Driven Design. Entities are referred to by an identifier, and instances of value types compare by their content. This is also, why a value type instance is not expected to be changed, since it would compare differntly at different stages during its life cycle. |

Scope Variability Split

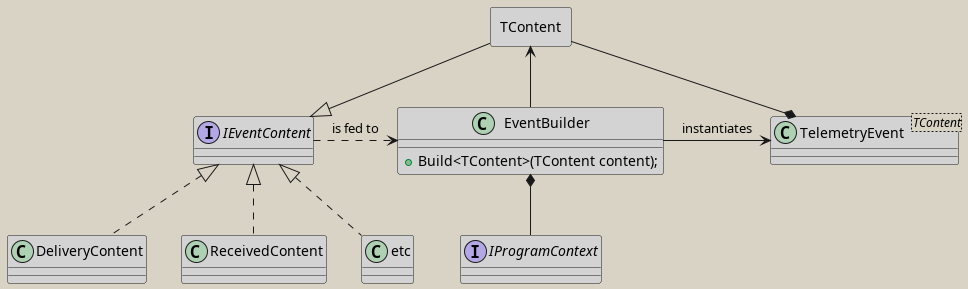

A clean design can be obtained by splitting the events by feature specific properties and generic properties.

interface IEventContent

{

public string EventType { get; }

}

class TelemetryEvent

{

public Guid UserId { get; set; }

public Guid SubscriptionId { get; set; }

public required IEventContent Content { get; set; }

}

class OcpCompliantDeliveryContent : IEventContent

{

public TimeSpan DeliveryDuration { get; set; }

public string EventType => "Delivery";

}Then, it is possible to provide a tracking service with the dependencies needed for any event.

class EventBuilder

{

private readonly IProgramContext _programContext;

public EventBuilder(IProgramContext programContext)

{

_programContext = programContext;

}

public TelemetryEvent Build<TContent>(TContent evt) where TContent : IEventContent

{

return new TelemetryEvent {

UserId = _programContext.UserId,

SubscriptionId = _programContext.SubscriptionId,

Content = evt

};

}

}To summarize:

The code in Listing 5 is compliant to the Open Closed principle and it also complies to the DRY principle. There is one slightly negative consequence: There is not just one single place in the code base that contains all the events. But: if you list all implementations of IContent, all events are actually listed. This fact can be used to create a program that uses reflection to determine all events, maybe generating some well styled html document, so product managers can get an idea, what they are searching for.

List entity configurations into categories

Another OCP violating example I came across is found in a repository that contains plenty of configuration files in JSON format. In essence, there are two kinds of files, each kind of file stored in its own folder. Say there is one folder that contains declarations of resources, one in each file.

{

"identifier": "AA",

"displayName": "The first in a row"

}The other folder contains structures that reference the resources. Let’s call them aggregates.

{

"identifier": "aggregate-RF",

"resources": ["AA", "AC", "BT"]

}Further assume that these configurations live in a repository that has the purpose to provide a self service for vertical product teams. If a vertical team would like to have some resource available in a technical platform, such an aggregate configuration has to be provided that references actual resources. Since the vertical teams are solely interested in bringing the actual resource into the platform, their focus is on declaring the resources themselve, carefully. Furthermore, assume that the configuration of the resources is actually a complicated undertaking, and it is done very rarely.

What happens on a regular basis, is that the resources are declared, but not the actual aggregates. Code changes are made by the vertical teams and pull request approvals are done by a horizontal team. Therefore, the turn around time is rather large. After about a day, it is realized that the changes do not have the desired effect. As a response a support channel is used to ask for help. The horizontal team starts debugging into the issue and finds that the resource is not added to any aggregate. Another pull request is created, and after two days the desired change is landed.

The root cause of this problem is, that the Open Closed principle is broken. We have to modify the aggregates to get the desired effect, in addition to creating the actual resources.

To comply to the Open Closed Principle, we can remove the resources property from teh aggregates and add a reference from the resources to the aggregates.

{

"identifier": "AA",

"displayName": "The first in a row",

"aggregate": "aggregate-RF"

}By this, analogously to Scope Variability Split, a catalogue is removed to adhere to the Open Closed Principle.

Data catalogue

This example is a cloud native example, in which several HTTP services interact with each other. There are several services that each represent a data type, which we are going to call data services. A data service can serve data products.

|

Note

|

While the term data product is used here, I do not want to connotate a data mesh architecture. A data product just refers to an instance of a REST resource of a data service. |

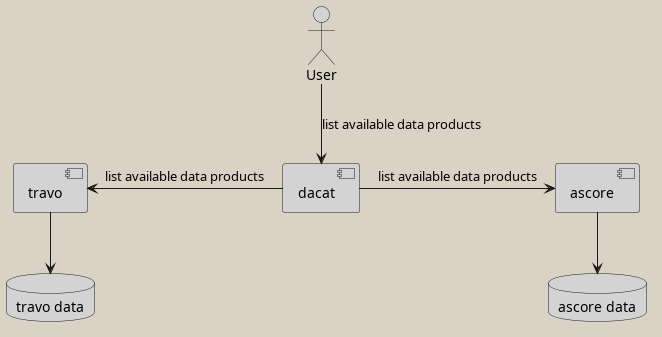

For example ascore that provides a certain kind of data in a specific form, or travo that provides a different kind of data in a different form. Then, there is a central service that is called dacat, which represents a data catalogue. It’s purpose is to show all data products that are served from the data services. The naive service interaction might be that the data catalogue calls the data services to query, which data products are available for each.

Adding a new data service is a two step process: First implement and deploy the data service, and then make changes to the data catalogue, so it uses the new data service. This is not severe at a first glance, since the addition of a new data service happens rarely.

But it can become a severe problem, if the environment together with its organizational structure evolves. It might happen that the product line that is opened up to customers is a big success. Then, what will happen is, that more data services are going to be developed, and that the data services are devloped in teams that do not maintain the data catalogue. This makes sense, since the data catalogue itself requires engineering skills, but no data science skills. That means, that as soon as a new data service appears, a requirements must be formulated by the implementors to have it registered in the data catalogue. If you’re living in an organization that complies to the SAFe process, you might need to wait some months until you can go to market after the data service implementations finished.

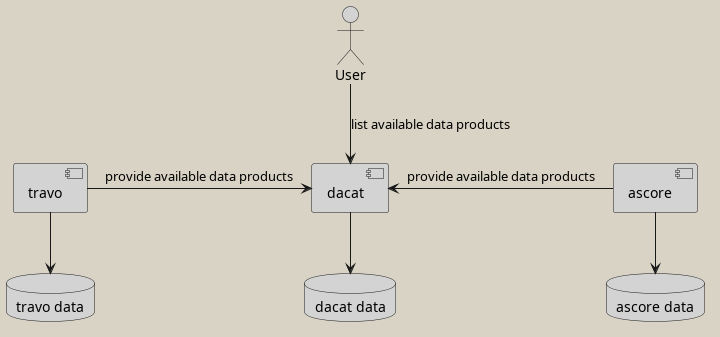

To cope with that issue, dependency inversion on the service level can be performed. Instead of the data services being called by the data catalogue to obtain data product lists, the data services call the data catalogue, to inform it about their data products. Typically, this is done asynchronously by messaging, which even decouples the system temporarily.

This variant allows to let several teams to interact technically, without the need for cross team communication, by that tremendously reducing the time to market for new data products. Obviously, this comes at a cost: The meta data about data products is redundantly stored and the communication pattern is a bit more complicated to implement.

Summary

In the first OCP violating example Generating telemetry events, a catalogue was removed, to relieve the implementor from the tradeoff with the DRY principle. Code duplication could simply be avoided by splitting a basic datastructure, instead of sharing common dependencies in a catalogue.

In the second example List entity configurations into categories, the probability of making additional turnarounds in an environment with long turn around times is reduced by complying to the Open Closed Principle for data. Instead of catalogizing resources the catalogue assignment can be deduced from the resources themselves.

The third example Data catalogue shows that huge impacts on development scalability can occur if the Open Closed Principle is not followed on the service level, when multiple components are involved.

In short: Breaking OCP does not scale!